| | | | | | | Presented By OurCrowd | | | | Codebook | | By Zach Dorfman of the Aspen Institute ·Jul 01, 2020 | | Situational awareness: Financial transfer data intercepted by U.S. intelligence backed agencies' report that Russia was offering the Taliban bounties to kill American soldiers in Afghanistan, the New York Times reports. Today's newsletter is 1,543 words, a 6-minute read. | | | | | | 1 big thing: New bill stokes long-running encryption fight |  | | | Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios | | | | Congress is gearing up for another run at passing encryption laws that proponents say will allow U.S. law enforcement to do its job and security experts say will make everyone's communications less safe. The big picture: As companies like Facebook and Apple encrypt more of their platforms by default, U.S. authorities fear the world is "going dark" on them. Meanwhile, the consensus is stronger than ever among security experts, human rights advocates and the industry that weakening encryption hurts everyone. Driving the news: Last week, Sens. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) and Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.) introduced the Lawful Access to Encrypted Data Act, which would force makers of devices, platforms and apps to create backdoors so law enforcement can access communications and metadata on these platforms and crack devices open as well. - "Tech companies' increasing reliance on encryption has turned their platforms into a new, lawless playground of criminal activity," said Cotton in a statement accompanying the bill's announcement.

According to the proposed law, use of these access capabilities, for both criminal and national security investigations, would require a warrant. But mandating potential backdoors in popular messaging apps like WhatsApp would uniformly weaken these platforms' security, say experts. - The bill is a "full-frontal nuclear assault on encryption in all its forms," says Riana Pfefferkorn, associate director of surveillance and cybersecurity at the Stanford Center for Internet and Society.

Be smart: Data is either encrypted or it's not. The creation of a vulnerability for use by U.S. law enforcement provides opportunities for malign foreign states like Russia and China as well as cybercriminal groups. The catch: Critics argue the bill would be unlikely to fulfill its stated objective — making it easier for U.S. law enforcement to access encrypted communications among criminals, terrorists and spies. - Sophisticated malign actors like terrorists and child predators will move their communications onto bespoke encrypted platforms or burrow into the dark web.

- And technologically savvy, privacy-concerned Americans may be able to simply procure encrypted messaging platforms produced outside of the U.S. in places where strong encryption isn't functionally outlawed.

- Lawful Access to Encrypted Data Act would also force device manufacturers to create backdoors, for instance on iPhones. These devices are used extensively all over the world, so the bill could expose device holders globally to potential surveillance — and much worse — by bad actors.

"You are creating a world where criminals have better security than law-abiding citizens do," says Pfefferkorn. The intrigue: Pfefferkorn believes that the act's backers aim to make another bill that could weaken encryption, the EARN IT Act, appear more reasonable. Both should be rejected, she argues. - The EARN IT Act aims to curb child exploitation online by tying changes to liability protections for tech platforms to government-mandated "best practices" that could involve back-door requirements.

- Wednesday morning, Graham introduced a substantial modification to the bill, and its provisions appear to be in flux.

The state of play: The debate over encryption has smoldered and flared periodically for decades, with government authorities — led, today, by Attorney General William Barr — insisting on their need for access and security experts warning that backdoors harm everyone. - But this time around, the encryption push is not even uniformly supported within federal law enforcement circles.

- "It is time for governmental authorities — including law enforcement — to embrace encryption because it is one of the few mechanisms that the United States and its allies can use to more effectively protect themselves from existential cybersecurity threats, particularly from China," wrote former FBI general counsel Jim Baker in an important essay in Lawfare earlier this year.

My thought bubble: Thus far, the "lawful access" debate has centered on how encryption affects law enforcement. But its impact on U.S. intelligence agencies has flown almost entirely under the radar. - Spying is being transformed in the digital age. Governments still view human intelligence-gathering as essential, but ubiquitous interception, tracking and surveillance technologies have made it more complex than ever.

- Intelligence officers need to be able to communicate securely without harming sources. Asking those sources to use bespoke covert communications tools could endanger them.

- Consequently, America's spies have turned to "hiding in plain sight," integrating their espionage tradecraft into mundane digital life, where it's less likely to be noticed by adversaries or endanger sources. This likely includes using strongly encrypted, commercially available apps and devices for communications. Compromising that tech would also compromise their intelligence work.

The bottom line: So far, the Department of Justice and domestic U.S. law enforcement agencies have dominated the "lawful access" debate. Intelligence agencies, loath to reveal sources and methods, have said nothing publicly. - But this is one instance where greater transparency from the U.S. intelligence community may make us all — including America's own spies — safer.

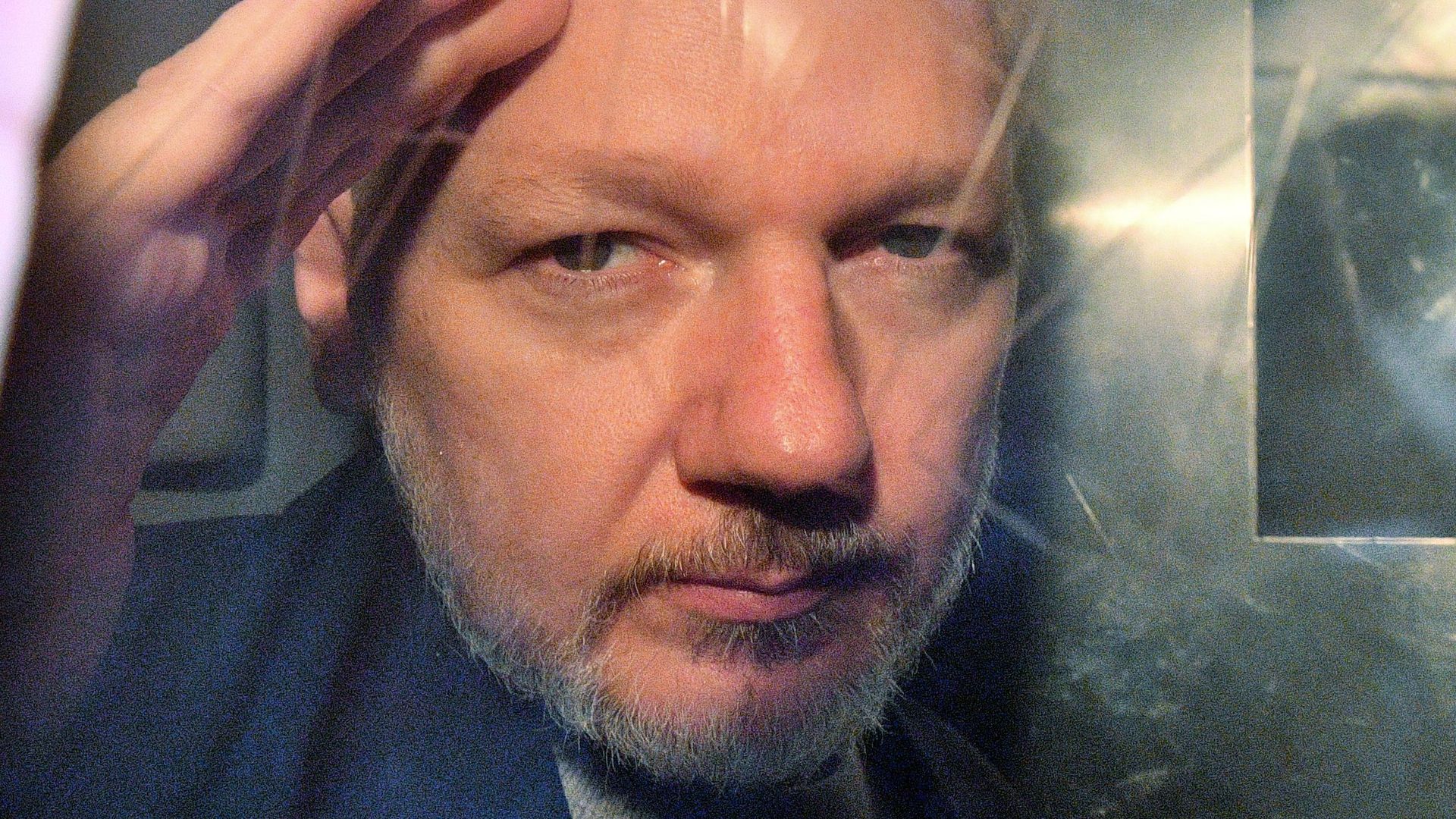

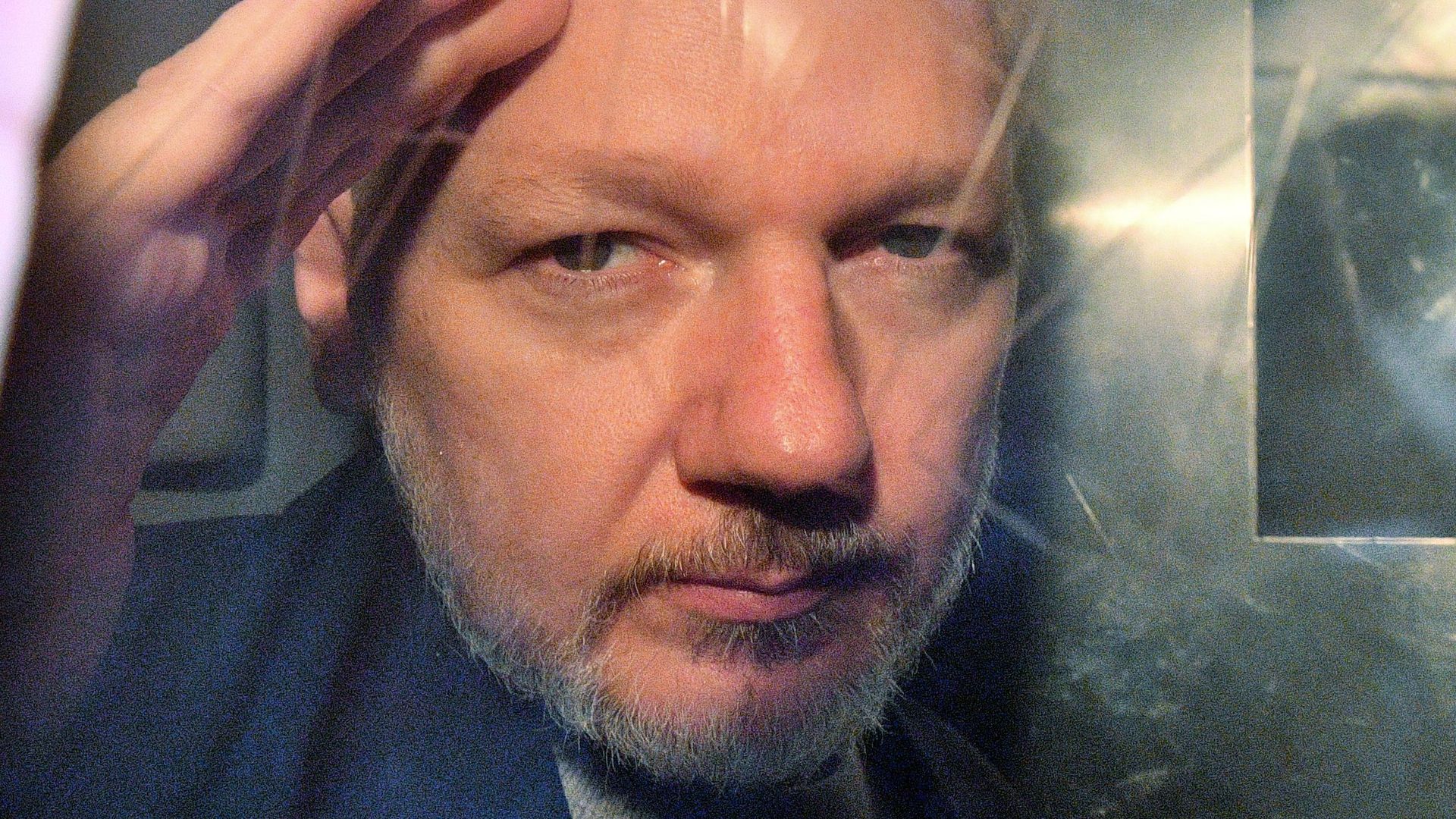

|     | | | | | | 2. What's in the new version of Assange indictment |  | | | WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange gestures from the window of a prison van in London on May 1, 2019. Photo: Daniel Leal-Olivas/AFP via Getty Images | | | | Last week, DOJ officials unsealed a new, superseding indictment against WikiLeaks chief Julian Assange. Why it matters: While the new indictment does not include new charges, it fills in important details on Assange's alleged conduct — which, if true, place Assange's behavior far outside the bounds of mainstream journalism. - The new indictment claims that Assange asked someone affiliated with the hacking group LulzSec — who was then working with U.S. officials, unbeknownst to Assange — to hack specific entities and look for certain types of documents that could then be published on WikiLeaks' site.

- Assange also worked with Chelsea Manning to break open a password on a Department of Defense computer, say prosecutors.

- The new indictment also alleges that Assange asked a hacker to try to gain renewed access to the internal networks of Stratfor, a private security intelligence company.

The big picture: Throughout his decade-long fight with the U.S. over Wikileaks' publication of government documents, Assange has maintained that he worked as a journalist. - But working with individuals to hack specific governmental or private entities, and tasking others to do so, is completely outside the bounds of journalistic practices and ethics. If that's what Assange did, the First Amendment won't offer him much protection.

Yes, but: Assange is not simply being indicted on charges related to attempted computer intrusions. He is also being charged with violations of the Espionage Act, a widely criticized law that can be interpreted to criminalize the legitimate practice of journalism. - Indeed, according to earlier reporting, Obama-era DOJ officials declined to prosecute Assange on Espionage Act violations for fears of the chilling effect such a move might have.

- Trump-era DOJ officials say the Assange indictment is not out to set a precedent for using the act against journalists.

- But the fact remains that they are prosecuting Assange not just for a hacking conspiracy but also for merely publishing certain information. That's worrisome for defenders of press freedom.

|     | | | | | | 3. UCSF paid $1.14 million ransomware demand | | The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), one of the country's foremost medical research facilities, was forced to pay over $1 million to a shadowy cyber criminal group dubbed NetWalker that had encrypted the hospital's data, according to a BBC report. Why it matters: UCSF has been a key global institution in helping develop a vaccine to COVID-19. Details: IT personnel at UCSF raced to shield sensitive records from the cyber criminals, and NetWalker did not steal personal patient medical records or COVID-19 research, said UCSF in a statement. - However, "the data that was encrypted is important to some of the academic work [UCSF] pursue[s] as a university serving the public good," so the university paid the ransom, it said.

The intrigue: After the June 1 ransomware attack, the BBC, following a tip, was able to observe negotiations on the dark web between UCSF and NetWalker over decrypting the university's data. - At first, NetWalker demanded $3 million from UCSF. Over time, however, the university managed to negotiate the cyber criminal group down to "only" $1.14 million, according to the BBC report.

- NetWalker demanded payment in Bitcoin.

- UCSF is now working with the FBI on the follow-up investigation into this brazen act of cyber crime.

|     | | | | | | A message from OurCrowd | | Beyond Meat investor opens new food-tech investment opportunity | | |  | | | | OurCrowd is creating access to pre-IPO opportunities like food-tech company Ripple Foods. The idea: Going beyond dairy, Ripple utilizes its groundbreaking technology to make plant-based milks that are great tasting, high in protein — as high as dairy milk — and much lower in sugar. Find out more. | | | | | | 4. At-home workers targeted by password thieves | | With so many people working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic, more cyber criminals are using "brute force" attacks to break the passwords of employees signing into their company networks remotely, according to ESET, a cybersecurity and antivirus protection firm. How it works: Brute force attacks break into systems by trying out vast numbers of possible passwords. - Cyber criminal groups are targeting increasingly ubiquitously used remote login services as a way to circumvent the usual protections to company systems.

- The criminals then often hold companies' networks hostage via ransomware.

What they're saying: "Despite the increasing importance of [remote access services], organizations often neglect its settings and protection," writes ESET. - "Employees use easy-to-guess passwords and with no additional layers of authentication or protection. ... Cybercriminals typically brute-force their way into a poorly secured network, elevate their rights to admin level, disable or uninstall security solutions and then run ransomware to encrypt crucial company data."

Of note: Among ESET's own users, the most commonly blocked IP addresses associated with these types of attempted intrusions came from the United States, China, Russia, France and Germany. - Meanwhile, most victims of these types of attempted intrusions possess IP addresses located in Russia, Germany, Japan, Brazil and Hungary, says ESET.

|     | | | | | | 5. Odds and ends | | |     | | | | | | A message from OurCrowd | | OurCrowd creates pre-IPO investment opportunities for individuals | | |  | | | | OurCrowd brings accredited investors world-changing pre-IPO opportunities – like Silicon Valley food-tech startup, Ripple Foods. The product: Ripple's great tasting, high protein, low sugar, plant-based milk products are currently being bought by customers in over 15,000 stores. Find out more. | | | | | | Axios thanks our partners for supporting our newsletters.

Sponsorship has no influence on editorial content. Axios, 3100 Clarendon Blvd, Suite 1300, Arlington VA 22201 | | | You received this email because you signed up for newsletters from Axios.

Change your preferences or unsubscribe here. | | | Was this email forwarded to you?

Sign up now to get Axios in your inbox. | | | | Follow Axios on social media:    | | | | | |