(electrofervor/Flickr)

Sadly, the men credited with inventing the color test pattern haven't gotten a ton of public recognition for it

Let's say you're floating around an obituary page in a newspaper—let's say the Los Angeles Times—and you see this line crop up:

He earned his engineering and electronics degrees from Lehigh University and his master's from Princeton University. Dave had a distinguished career with 13 patents to his name, including the color television and the color test pattern.

This guy has a patent for inventing the color TV? And there's not a reported obituary about his life?

That was an experience that readers of the Times could have had in August of 2018, when an obituary for the 91-year-old Norbert David Larky (who generally went by his middle name) ran in its newspaper.

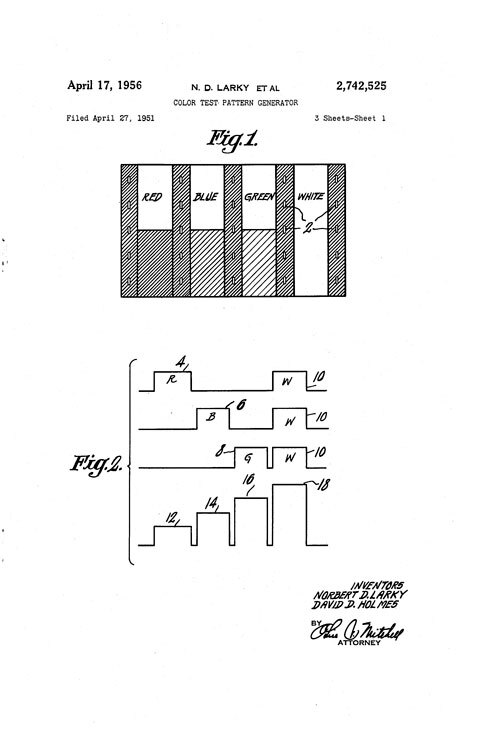

The first patent filing for the color pattern test generator. (Google Patents)

Clearly, this was a missed opportunity for the L.A. Times, which heavily covers the entertainment industry, as Larky (along with David D. Holmes) legitimately did receive the first patent for the color test pattern generator, which was granted in 1956 after being filed for in 1951.

The color TV concept does predate Larky, but as an employee of early color television innovator RCA, he did develop some key patents on that front.

(To be clear, is evidence that Larky and Holmes have received the initial patent for this invention, though others were, without realizing it, competing with them around the same time. For example, Charles J. Hirsch of the technology company Hazeltine wrote a lengthy piece for the academic journal Advances in Electronics and Electron Physics in 1953, in which he described that company's work on color television, including a discussion on the creation of color bars.)

These test bars, throughout their evolutions—with the most recent occurring in 2002 to account for the HDTV switch—remain important in the television industry, as they allow engineers to adjust color schemes to correctly match what's on the screen and modify accordingly.

But, thinking bigger picture, they also represent some of the first electronically produced graphics ever displayed on a screen—a pretty significant development in a world where graphics are basically everywhere. (Graphics, while a fundamental part of computing today, didn't truly become mainstream on computers until the 1970s, when terminals transferred from printers to monitors.)

An example of a black and white test pattern from the mid-1950s. The "Indian head" test pattern of the era is better known, but it's a relic of the past that doesn't really need to be displayed anymore. Plenty of places to find that stereotyped image on the internet. (1950sUnlimited/Flickr)

Before those color bars, a wide variety of different black-and-white images were used, most notably the "Indian head" graphic created by RCA in 1938, which became the first popular test image of the era.

Writer John R. Meagher explained in a 1948 Radio Electronics article the necessity of these test patterns at the time. Essentially, early televisions needed much more in the way of constant tuning, which meant that guidelines that helped owners test for the curve of the picture, the overall focus, the shading, and for interlacing were necessary.

"There is no standard test pattern in general use. The nearest thing to a standard is the RCA 'Indian head' monoscope, which is used by a number of TV stations," Meagher wrote. "[The Radio Manufacturers Association] has proposed a standard 'resolution chart,' but for various reasons it has not been adopted by TV stations for air use."

During the early television era, this image showed up multiple times a day on some channels, along with an accompanying sine wave tone.

Over time, color bars became even more familiar to TV viewers than the black and white equivalents. (Probably a good thing, as the black-and-white test pattern used a stereotypical image of Native Americans!)

Beyond its technical reasons for existence—initially, it was used for calibration in early color televisions, and is today used as a way to ensure chroma and luminance levels in modern screens of all types—it became a pop culture icon of its own. The mobile game show HQ Trivia, for example, directly riffs on the color bars just before a game starts, integrating a modern twist on a vintage look. And Elliott Smith wrote a song about them.

TV pictures eventually became much easier to keep tuned, which meant that the reasoning for the regular use of color bars was less essential on a regular basis, but they became a part of the fabric of modern life, especially on cable channels that didn't have enough content to fill out an entire day.